This post was inspired by recently reading Jeff Augen's (in many ways disappointing) book Trading Realities". Augen comments that the moves in the US stock markets can be largely explained by currency fluctuations. I decided to investigate the relationship, and rounded up the following ETFs (all of which are preferable to "raw" instruments, since they keep track of dividends and such, and all have a rather low expense ratio:

- SPY -- a proxy for the S&P 500 (with dividends reinvested.)

- IWM -- a proxy for the Russell 2000 (with dividends reinveste)

- GLD -- a proxy for physical gold (notorious for not paying dividends)

- FXA -- a proxy for the Australian Dollar (pays interest, roughly equal to the Australian Central Bank overnight rate).

- FXE -- a proxy for the Euro (pays interest, just as, though not as much as, the Ozzie)

- FXF -- a proxy for the Swiss Franc (pays interest, as above).

The newest of these instruments have been around since 6/26/2006, so I picked that date as the start of my study, while 5/20/2011 was the end. First, I wanted to compare the returns of all the six instruments, and produced the following graph:

This was a bit of a shock: you will notice that while gold is the master of all it surveys, buying and holding (in a money market account) the Ozzie or the Swiss Franc produced a better return than investing in the US stock market (large

or small cap). Even buying and holding the Euro did as well as the S&P 500! The most depressing thought for those of us investing money in hedge funds is that the simpleton buying and holding FXA (let's not rub it in by talking about gold -- we have time enough for that below) would have outperformed the majority of hedge funds over the same period.

But more shocks were to come. The charts below show how well a European, a Swiss, or an Australian would do investing in the US stock market, compared to a compatriot who decided to keep her money in a mattress:

The above graphs, especially the last two, surprised me: notice that the US equity markets start a precipitous decline in mid-2007, have a V-shaped dip reaching its nadir in early 2009, but

do not ever recover beyond October 2010 level (to the present day). This is less true when the comparison is made with the Euro, but this just goes to show you that the Euro is almost as weak a currency as the USD. The conclusion seems inescapable: the recovery (at least of the equity market) is completely fake, and is caused entirely by Bernanke's helicopters circling overhead.

The last part of our analysis can be entitled:

What Gold Bubble?

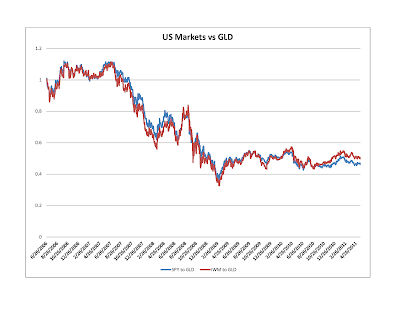

Let us see how investing in the US markets would have done compared to your retro gold-hoarding neighbor:

The short (and unsurprising) answer is: terribly. Just as in the ancient joke, the way to make a kilo of gold in the stock market is to start out with two kilos. What, however, is much more (to me) surprising is that the collapse (in gold terms) started in 2007, and ever since (again) October 2010 the US equity market has actually maintained parity against gold, although the same cannot be said about the US dollar. Our final chart drives the point home. The chart shows the performance of gold when measured in the four currencies of this study (US dollar, Euro, the Swiss Frank, and the Australian dollar):

If you look at the chart carefully, you will see that gold peaked against the "hard" currencies in late 2008, and since then has been quite flat in both Swiss Franc and Australian Dollar terms (REALLY flat for the last year or so). So, there is no gold bubble currently (there might have been one leading up to 2008, but it was not really a bubble, since it had never popped. At worst, there was a mini-bubble in late 2008, which deflated and than reflated). What there appears to be is an ongoing collapse of the dollar, with no sign of abating.

What to do?

Other than getting very depressed... The good news is that with the exception of the Australian Dollar, the other instruments described in this post are almost uncorrelated to the US equities. While I would not touch the Euro with a barge pole (I believe that it is fundamentally as weak as the US dollar), and since the AUD has much better fundamentals than the swiss franc and gold, I see no downside in holding some mix of the the three (FXA, FXF, GLD, or the underliers) to at least diversify away some of the US equity (or currency) risk.